Reflections from a parish priest, dad and so-called theologian, living on an urban 'outer estate' in the West Midlands, on day-to-day life, faith, 'community', politics... and whatever else happens to turn up!

Labels

abundance / scarcity

(10)

advent

(8)

anger

(7)

anthropology

(2)

asset-based approaches

(20)

Big Society

(14)

brokenness

(15)

celebration

(4)

children

(4)

Christmas

(3)

Christology

(2)

church

(25)

co-production

(5)

Common Wealth network

(2)

community

(31)

community development

(11)

compassion

(3)

consumerism

(4)

death

(12)

desert

(2)

desire

(2)

employment

(6)

friendship

(11)

good news

(3)

government cuts

(22)

gratitude

(5)

home

(4)

hope

(20)

hospitality

(8)

housing

(1)

humility

(5)

imagination

(9)

improvisation

(9)

incarnation

(12)

lament

(10)

Lent

(1)

listening

(4)

liturgy

(1)

local economy

(2)

love

(6)

love your neighbour - love your enemy

(4)

neighbours

(18)

Occupy

(8)

patience

(5)

peace-making

(10)

prayer

(3)

presence

(5)

reconciliation

(5)

regeneration

(7)

resilience

(13)

resistance

(19)

resurrection

(12)

rich and poor

(16)

sabbatical

(8)

social inclusion

(6)

sustainability

(4)

sustainable livelihoods

(1)

trust

(4)

violence

(4)

waiting

(8)

witness

(4)

Search This Blog

Wednesday, 12 April 2017

The 'Robin Hood' restaurant and Christian mission

"Charge the 'rich' to feed the poor: Madrid's Robin Hood homeless cafe". So ran the headline in a heart-warming Guardian article about a Spanish restaurant that uses the takings from paying breakfast and lunch customers, to fund free evening meals for local homeless people. The article was picked up by a senior colleague in my diocese, who wondered if we might be able to try something similar in Birmingham. That wondering raised, for me, several important and very timely questions.

On the one hand, what's fantastic about this Madrid restaurant is that it treats all its customers with equal dignity and respect. In the evening, as much as in the daytime, the tables are laid with tablecloths and candles, the food is just as good, as is the service from the waiters. This cafe doesn't just feed people who are homeless, it treats them with the reverence deserved of any human being but which often in our world is only given to those who can afford to pay for it.

The 'Robin Hood' cafe (its name chosen very deliberately) also creates a channel for a small redistribution of wealth: the rich pay a bit more for their food, the cafe owners make a bit less profit, and the 'poor' (interesting how the Guardian article problematises the label 'rich' but not its opposite) get a decent meal. A more sustainable charitable model, perhaps, than relying on donations to run a soup kitchen. It's almost as if the 'donors' are enabled to give painlessly, without a second thought - or even affording them a rosy glow of goodness to accompany their tasty dessert.

And that, I think, is precisely the problem with this otherwise inspiring story. The richer diners get their decent meal, their conscience salved, and they don't have to think too hard about those who will eat in the same restaurant later in the day. Like any other monetary giving, it can be done at arm's length, without the disturbance or discomfort (dare I even suggest 'disgust' might sometimes be at work here?) of an actual encounter with those on the receiving end. The maitre d' and the waiters do that bit, of course, however 'heroically'. But they are also paid to do their job. Those who pay to consume (both food and the badge of charitable goodness) can, like most consumers, isolate themselves from their neighbours in their little bubbles of consumption.

Which brings me, disturbingly, to church. I'm not going to launch a full-on assault here on 'consumer Christianity', where you (the consumer) choose your brand, go for your 'fill-up', and move on somewhere else when it's not working for you any more. No, plenty of others have got that base well and truly covered. What I'm struggling with here is 'charitable Christianity', and I'm pretty sure most of us Christians are well and truly embedded in it. It operates on a very clear and simple model: we go to church to 'fill up', and then we're sent out into the world to 'give out'. If you're from a more evangelical tradition, you might hear the gospel in church, and preach/share it in the world. If you're of a more catholic persuasion, you'll be fed with the eucharist in church, and then disperse, like the broken bread, to feed others. In the Church of England eucharistic liturgy, this logic is laid out very clearly in one of the two post-communion prayers: "may we who drink his cup bring life to others, we whom the Spirit lights give light to the world" - a logic echoed in the strapline for Church of England Birmingham's new 'resourcing church' when it proclaims it wants to be "light for the city", "bringing hope and light to Birmingham".

Now all of this is, at the very least, half of the truth. The trouble begins when we make it the whole truth. If we are to preach the word, then others must be the listeners. If we are fed to feed others, then those others have nothing that might nourish us in turn. If we are the "light for the city", then where we are not is, implicitly at least, in the dark.

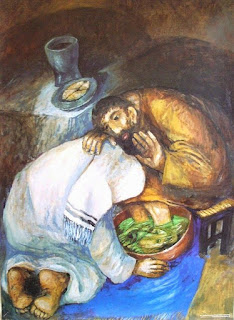

In the gospels, it is Peter more than any other who is confronted with the half-truth nature of these beliefs. Peter is well-practised at getting things 'half-right': "you are the Messiah", he proclaims, before instantly getting it terribly wrong when he refuses to let Jesus take the path of suffering laid out before him. But the moment I have in mind here comes later on, at Jesus' 'last supper', when Jesus kneels down and attempts to wash Peter's feet. "You wash my feet, Lord?!" Peter protests. Surely it should be the other way round?! Peter has 'got' the idea of 'service', it seems - but can't get his head round being on the receiving end.

I love Maundy Thursday (the Thursday before Easter) precisely because it's the day of the year we get to re-tell that story, and re-enact it too. We're invited to confront the sweaty, dirty, mis-shapen awkwardness of each other's feet, and to get up close and personal with them with a bowl of soapy water. And while it's a privilege to be involved in doing the washing, it's the being washed that seems always to be the hardest part. Women with tights have a particularly convincing reason for finding it difficult. But it's not just a logistical challenge. There seems to be something that goes very deep within most of us that, like Peter, resists letting someone wash our feet. Disturbance, discomfort, disgust, maybe. But more basic than any of those, simply being on the receiving end. Being touched. Being 'served', without retaining the power of paying for it. Little wonder, that even among my wonderful congregation in Hodge Hill, at most only 50% of those who come to Maundy Thursday service are usually game enough to have their feet washed.

Now I don't believe there's anything particularly magical about foot-washing that inherently disrupts the logic I laid out above. I know of plenty of Maundy Thursday stories of Christians going out of church to wash the feet of their neighbours - either literally or metaphorically (shoe-shining seems to be a popular version at the moment, at least among communities where shiny shoes are more the norm). If the more sacramental among us did foot-washing rather than eucharist every Sunday, you can bet we'd be having our feet-washed to go out and wash others' feet as a matter of course.

But what foot-washing does have over preaching the gospel and breaking bread is the in-built element of disturbance, discomfort and disgust attached to being on the receiving end of it. It could never (I think) be something received easily, casuallly, without an degree of awkwardness about it. And maybe that's precisely why Christians haven't adopted it as a central, weekly practice. Maybe that's why it's not central to the anneal gathering of clergy in Anglican cathedrals that happens every Maundy Thursday morning (even if it may be talked about in readings and sermons in those gatherings). Maybe learning to have our feet washed can teach us something about an openness to receiving strange, awkward, holy gifts from our neighbours - rather than allowing ourselves to imagine that we're always sent out of church to 'bring' something, 'give' something to others?

In our neighbourhood over the last few weeks, a wonderful and rapidly-growing team of volunteers have started a weekly cafe, in partnership with The Real Junk Food Project, cooking and serving food that would otherwise have been thrown away by major supermarket and restaurant chains. The meals themselves are of the best quality, and the service is warm and friendly. One of the distinctive things about our Real Junk Food Kitchen is that it operates (like all TRJFP cafes) on a "pay as you feel" basis: you can pay money for your food (if you want to and are able), or you can pay by contributing your time, skills and gifts (to the cafe, or to other things happening locally) - or both! Where our cafe differs from Madrid's 'Robin Hood', then, is that there are no separations between those who can pay and those who can't - in fact, few people will notice who is who. We all eat together, and in the process, make friends across our differences, and receive the gifts each other brings. Those of us who feel less comfortable being on the receiving end just have to get over ourselves (including un-learning our consumerist and charitable tendencies) and learn to welcome the (sometimes strange) gifts that come to our tables. There's something pretty Easter-y about that, I'd suggest...

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

very interesting hands on approach, it's this type of Spirituality which is needed, should be welcomed, instead of sitting in church pews smiling to ourselves. hopeful you will attend Lee Abbey 7 July about new religious communities

ReplyDeleteAwe-inspiring blogs, I love reading your articles.

ReplyDeletewww.milan.precondo.ca