In this time

when we’re not able to share communion together, this guided reflection offers

an opportunity for each of us to meet Jesus in the breaking of bread, in our own home, wherever we are. It was intended for use at any time in these weeks where we’re

cut off physically from each other – but has special significance this week, as

it’s based on this Sunday’s gospel reading.

Walk through the reflection slowly. Give it time. One

of the many, many insights of this story is, as Japanese theologian Kosuke

Koyama puts it:

God walks “slowly” because he is

love. If he is not love he would have gone much faster…. [Love] goes on in the

depth of our life, whether we notice or not, whether we are currently hit by

storm or not, at three miles an hour. It is the speed we walk and therefore it

is the speed the love of God walks.’

Emmaus Road, by He Qi

With Jesus on the road:

‘what things?’

13 Now on that same day two of them were going to a village called

Emmaus, about seven miles from Jerusalem, 14 and talking

with each other about all these things that had happened. 15 While

they were talking and discussing, Jesus himself came near and went with them, 16 but

their eyes were kept from recognizing him. 17 And he

said to them, “What are you discussing with each other while you walk along?”

They stood still, looking sad. 18 Then one of them,

whose name was Cleopas, answered him, “Are you the only stranger in Jerusalem

who does not know the things that have taken place there in these days?” 19 He

asked them, “What things?”

Imagine

you’re walking down that road, heading home, walking and talking with a friend

or loved one. Talking together about everything that’s going on in the world.

Imagine

Jesus comes alongside you, and asks you what you’re talking about. It’s an open

question: ‘what things?’

Tell

Jesus what’s been going on. Don’t worry that he’ll know already. Imagine him as

a friendly stranger, who’s a good listener. Tell him what’s important to you

right now.

With Jesus on the road:

hopes dashed, and a rumour of resurrection

hopes dashed, and a rumour of resurrection

They replied, “The things about Jesus of Nazareth, who was a

prophet mighty in deed and word before God and all the people, 20 and

how our chief priests and leaders handed him over to be condemned to death and

crucified him. 21 But we had hoped that he was the one

to redeem Israel. Yes, and besides all this, it is now the third day since

these things took place. 22 Moreover, some women of our

group astounded us. They were at the tomb early this morning, 23 and

when they did not find his body there, they came back and told us that they had

indeed seen a vision of angels who said that he was alive. 24 Some

of those who were with us went to the tomb and found it just as the women had

said; but they did not see him.”

‘We

had hoped…’, say the disciples. They share with Jesus their hopes and their

disappointments – and their shock and grief. And they share their wonderings,

however doubtful – a rumour of resurrection – the faintest of hopes, a tiny

glimmer of possibility of life beyond death.

Share

with Jesus what’s on your heart. Tell him how you’re feeling: the happy and the

sad, the hopeful and the fearful, the things you’re thankful for and the things

that are heart-breaking.

With Jesus on the road:

re-telling the story

25 Then he said to them, “Oh, how foolish you are, and how slow of

heart to believe all that the prophets have declared! 26 Was

it not necessary that the Messiah should suffer these things and then enter

into his glory?” 27 Then beginning with Moses and all

the prophets, he interpreted to them the things about himself in all the

scriptures.

It’s

probably not the response they were expecting! Jesus sounds a bit harsh here.

But if we can get over that, we hear him responding to their story-telling with

some story-telling of his own: helping them see how their fragments of

experience are in fact part of a much bigger Story, that stretches back to the

beginning of creation, and forward to the ‘making new’ of all things. And

helping them understand that he, Jesus, is in the middle of it all – with us,

in it all, every step of the way.

Where

might Jesus be in the midst of all that is going on right now? What words might

he be saying, to you, and to those others for whom you’re praying? What might

it mean, that our stories of suffering and death, of disappointment and fear,

are held within his story of love and healing, of death and resurrection?

Spend

some time listening for a word of hope and promise – or, in the silence, simply

know yourself in the company of Jesus.

Inviting Jesus in

28 As they came near the village to which they were going, he walked

ahead as if he were going on. 29 But they urged him

strongly, saying, “Stay with us, because it is almost evening and the day is

now nearly over.” So he went in to stay with them.

‘Stay

with us…’, the disciples say to Jesus. Invite Jesus to come into your home, to

stay – to be with you, here and now.

Imagine

opening your door for him, and welcoming him in. Imagine him coming in with

you, following you through your home and sitting down next to you where you

are.

A

hymn / prayer (especially for evenings):

Lord Jesus Christ, abide with us,

Now that the sun has run its course;

Let hope not be obscured by night,

But may faith's darkness be as light.

Now that the sun has run its course;

Let hope not be obscured by night,

But may faith's darkness be as light.

Lord Jesus Christ, grant us your peace.

And when the trials of earth shall cease.

Grant us the morning light of grace,

The radiant splendour of your face.

And when the trials of earth shall cease.

Grant us the morning light of grace,

The radiant splendour of your face.

Immortal, Holy, Threefold Light.

Yours be the kingdom, pow'r, and might;

All glory be eternally

To you, life-giving Trinity!

Yours be the kingdom, pow'r, and might;

All glory be eternally

To you, life-giving Trinity!

Text: Mane Nobiscum Domine;

Melody: Old 110th

Recognition…

30 When he was at the table with them, he took bread, blessed and

broke it, and gave it to them. 31 Then their eyes were

opened, and they recognized him; and he vanished from their sight. 32 They

said to each other, “Were not our hearts burning within us while he was talking

to us on the road, while he was opening the scriptures to us?”

Take some bread in your

hands, just as Jesus did.

Break it, just as Jesus

did.

Take a piece and eat

it.

‘Their

eyes were opened, and they recognized him…’

Know that Jesus is with

you, closer than breathing.

Spend some time just

dwelling in this moment, with thankfulness.

33 That same

hour they got up and returned to Jerusalem; and they found the eleven and their

companions gathered together. 34 They were saying, “The

Lord has risen indeed, and he has appeared to Simon!” 35 Then

they told what had happened on the road, and how he had been made known to them

in the breaking of the bread.

This

is where the story ends. For us, at the moment, there is an incompleteness.

It’s not possible for us to leave home, and return to a place where all our

friends are gathered together – where we can exchange our stories of where

we’ve met Jesus. We long for that day. We maybe even ache for it.

But

what is possible today, or tomorrow? Who can we speak to – on the phone, on a

doorstep, or at a window? Who can we share with, the glimpses we’ve caught of

the risen Jesus, of hope and life?

Jesus, beloved friend, we thank you:

for listening to us along the way,

for coming in to be with us here,

and for making yourself known

in the breaking of bread.

Stay with us, we pray,

and when the day comes,

go ahead of us into the world:

that we might see your presence and hear your voice

in loved ones, in strangers, in neighbours all,

as we join together to cry:

He is risen indeed! Alleluia!

for listening to us along the way,

for coming in to be with us here,

and for making yourself known

in the breaking of bread.

Stay with us, we pray,

and when the day comes,

go ahead of us into the world:

that we might see your presence and hear your voice

in loved ones, in strangers, in neighbours all,

as we join together to cry:

He is risen indeed! Alleluia!

What happens on the Emmaus Road, as the bewildered friends of

Jesus and the friend they’d thought they’d lost walk together, is ‘the

unfolding of a Person’ (these words are from Roland Allen, a theologian): as they

walk and talk, Jesus offers space for his friends to ‘unfold’ their lives,

their stories, in his company; and he too ‘unfolds’ for them his story – the

story they thought they knew, but had not, until then, grasped more than tiny

fragments of it.

And in the walking, and the unfolding, and their instinct to

want to carry on this conversation, deepen this relationship further, that is

behind their invitation to ‘stay with us’ – they begin to notice, realise, see

things that before they had not noticed, realised, or seen.

In these weeks of what many are calling ‘lockdown’, when so

much of normal life has been put on ‘hold’ (and who knows what our new ‘normal’

might look life after this?), I wonder if we might hear a deeper

invitation, an invitation from the God who is Love: to a journey, a

walking together; to a conversation, an ‘unfolding’ of ourselves to each

other; and to a noticing, a possibility of seeing with new eyes things

about the world, and its people and other creatures, that we have not ever seen

or noticed before.

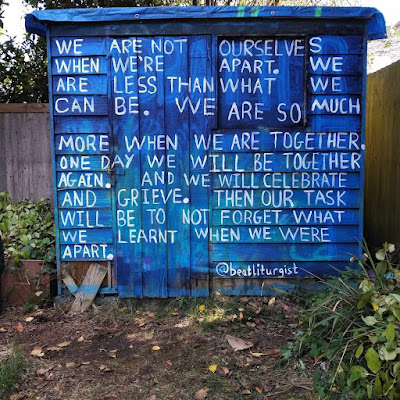

I’m going to finish with a picture, and a poem, that were

shared with me by a travelling companion of mine, a theologian of mission,

Cathy Ross. She reminds us that it is very often the people we tend not to

notice – the little ones, the ones on the edges, the ones who are rarely given

value – who see Jesus most clearly, and who will help us see Jesus more clearly

too. I wonder who, in our world today, we are beginning to notice more, value

more, and who might help us, in this time, begin to see Jesus afresh too?

Kitchen Maid with the Supper

at Emmaus, c. 1618, Velasquez

She listens, listens, holding

her breath. Surely that voice

is his – the one

who had looked at her, once, across the crowd,

as no one ever had looked?

Had

seen her? Had spoken as if to her?

Surely those hands were his,

taking the platter of bread from hers just now?

Hands

he’d laid on the dying and made them well?

Surely

that face?

The man they’d crucified for sedition and blasphemy.

The man whose body disappeared from its tomb.

The

man it was rumoured now

some women had seen this morning, alive?

some women had seen this morning, alive?

Those who had brought this stranger home to their table

don’t recognize yet with whom they sit.

But she in the kitchen,

absently touching the wine-jug she’s to take in,

a

young Black servant intently listening.

swings round and sees

the light around him

and is sure.