"Marsh reeds, when full grown, vary from five to ten feet in height, and the tassels on the ends of the good ones are thicker than squirrels' tails. The next time you walk past a bank of reeds, try something. Pick out the tallest one you can reach, and cut it off with your penknife as close to the ground as possible. Ostensibly, perhaps even to yourself, it will seem that you are cutting it down to carry home to your children. No one will take serious exception. But in the carrying of it, you will make a discovery. Keep a record of your reactions: It is impossible simply to carry a marsh reed. For how will you hold it? Level? Fine. But it is ten feet long, and plumed in the bargain. Are you seriously ready to march up the main street of town as a knight with lance lowered? Perhaps it would be less embarrassing to hold it vertically. Good. It rests gracefully in the crook of your arm. But now it is ten feet tall and makes you the bearer of a fantastic mace. What can you do to keep it from making a fool of you? To grasp it with one hand and use it in your walking only turns you from a king into an apostle... Do you see what you have discovered? There is no way of bearing the thing home without becoming an august and sacred figure... So much so that most people will never finish the experiment: the reed, if cut at all, will never reach home. Humankind cannot stand very much reality: the strongest doses of it are invariably dismissed as silliness. But silly is from selig, and selig means 'blessed'..." (Robert Farrar Capon, 'An Offering of Uncles', in The Romance of the Word, pp.45-6).The vast majority of us - especially those of us who live in urban areas like me and my neighbours in Firs and Bromford - will not have the opportunity to cut and carry a marsh reed for the foreseeable future. But Robert Farrar Capon, in his characteristically poetic and provocative style, describes here something which, I have a hunch, many of us have experienced in a whole variety of different ways over the last few weeks: the discovery that ordinary and everyday things - things we may not even have noticed or have tended to take for granted - are in fact something more, something more significant, something more remarkable, something more valuable, than we had realised up until now.

In Capon's terms - and he was an American Episcopalian (i.e. Anglican) priest - the bearer of the marsh reed is fulfilling the vocation of humanity: to be priests. What that vocation looks like for that small subset of people ordained by the Christian Church to be Priests (with a capital 'P', perhaps), has been something that the current COVID-19 crisis has somewhat thrown up in the air. I've already reflected on this a bit in some previous blog posts - especially on the temptations to the power of the provider, the performer and the possessor, and the im/possibility of 'sharing communion' when we are physically separated. Here, I want to take up Revd Dr Julie Gittoes' suggestion, that I reflected on in that previous post on communion, that as church we are living in an extended time of 'scatteredness', between the moments of eucharistic 'gathering', and that in this extended interval we might be learning more deeply what it means to live 'eucharistically':

"Perhaps this interval reveals the power of the sacrament: the space where we weave the eucharist into the daily life, and thereby transform it. The scattered Church thus continues to live and move, pray and serve, breath by breath — albeit over a longer and more difficult interval."What Julie names as 'living eucharistically', Capon calls 'the priesthood of humanity' - and he unfolds it, helpfully I think, in terms of place, time and history - terms that are, in our present times, being opened up for re-conceiving in ways that they have perhaps not been for a while. It is humanity's priesthood, Capon suggests, that refuses the abstractions of space (that can be mapped, engineered, packaged, bought and sold) and instead offers up the particularities and uniqueness, the storiedness and sacredness of place. It is humanity's priesthood that marks - notices, celebrates, mourns - chronological time ('chronos' in Greek), that measurable but uninteresting quantity (that at the moment seems, for many of us, to be dissolving even more than usual into an undifferentiated blur), in ways that discovers 'kairos' (Greek, again) time - 'real time', 'high time', as Capon puts it - time for things of significance, for noticing, for celebrating, for mourning, for loving, for living, for dying, for rising. And these priestly 'raisings' of 'space' and 'chronos-time' into 'place' and 'kairos-time' are, in Capon's way of framing things, about raising our mere 'chronicling of events' into something we might call 'history' - something with shape, direction, meaning, significance.

For Capon, it is no coincidence at all that this history of humanity's priesthood begins in a garden: 'And the Lord God took the earth-creature [adam, in Hebrew] and put it into the garden of Eden to till it and to keep it' [to 'serve and observe' it, as Hebrew scholar Ellen Davis has translated it].

"Look, Adam, he says. Look closely. This is no jungle; this is a park. It is not random, but shaped. I have laid it out for you this year, but you are its [gardener] from now on. The leaves will fall after the summer, and the bulbs will have to be split. You may want to put a hedge over there, and you might think about a gazebo down by the river - but do what you like; it's yours. Only look at its real shape, love it for itself, and life it into the exchanges you and I shall have. You will make a garden that will be the envy of the angels." (Capon, Romance, p.54)Capon, writing 40 years ago, even then was very aware of how humanity has both responded gloriously and failed desperately in our priestly vocation as 'earth-creatures'. Sylvia Keesmaat and Brian Walsh, writing much more recently, put it starkly in their reading of the Letter to the Romans:

"The point of many of the prophetic texts that Paul alludes to in Romans is that we have forgotten who we are. The earth creatures have failed to live up to the calling we were given, this calling to make the earth fully our home. This is what the language about exchanging the image of the living God is about... We have failed to be the ones who imaged God, and we have forgotten our roots in the earth. We are no longer the earth creatures but the death-bringers. We have replaced "till and keep" with "take and destroy." We have supplanted "serve and observe" with "dominate and discard." (Romans Disarmed, p.193)But what if this time, this time of so-called 'lockdown', is an invitation to be opened up: to our primary calling as earth-creatures, to the priesthood of all humanity? What if this time is an invitation to all of us to practise the arts some of us have been taught when learning how best to 'supervise' colleagues: to articulate well, within all our relationships, sentences (with or without words) that begin 'I notice...', 'I wonder...' and 'I realise...'? What if this time is an invitation to all of us to notice, wonder, and realise things about ourselves, our fellow creatures, our world, and the God who is in all of her creation - that we have either forgotten, or have never before known? And what if our noticing, our wondering, our realising flows into gratitude, thankfulness, a life that is 'eucharistic' (for 'eucharist', at its root, simply means thanksgiving)?

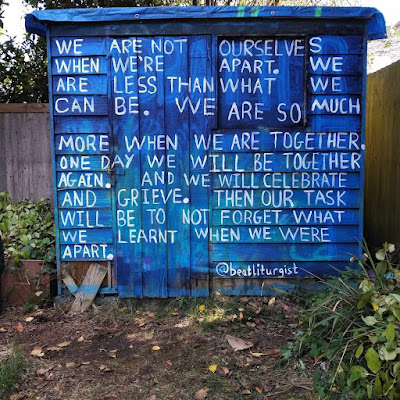

This is why our poets are so needed right now - and the particular kind of priesthood that they offer. And they are, thank God, stepping up to the moment. Lynn Ungar, Tim Watson (@beatliturgist), Arundhati Roy, Cormac Russell and Nicola Slee are among many who are offering us words as windows into the deeper realities of now - and I name these just because they are poets who have spoken to me. Barbara Brown Taylor's phrase 'an altar in the world' has resurfaced for me, especially: many of us are, I think, discovering such altars hidden in patches of woodland on our daily walks; we are learning that there are countless altars to be discovered in our world masquerading as hospital beds, supermarket tills, and bin lorries; and we are discovering too that our kitchen tables are so often such altars too.

Which brings me back to eucharist.

"For Christians, a sacrament is not a transaction - not an operation that produces an effect that wasn't there before... Take the Eucharist. And take the highest possible view of it: the bread and wine, at the beginning of the rite, are mere bread and wine; but when they are received by the faithful at the Communion, they are the body and blood of Christ - they are Jesus himself, really present in all of his divinity and all of his humanity, and in all the power of his death and resurrection. A question arises, however: Is this eucharistic "change of status" an ordinary, transactional alteration, like the change of flour into bread? Does the act of celebrating the Eucharist "mix up a batch of Jesus"? Does Jesus, during the service, show up in a room from which he was previously absent? Do benefits we were formerly without suddenly begin to flow our way in Communion?

"The answer to those questions, I think, has to be a flat no... It's not that their tank was topped off with Jesus the previous Sunday but now needs a refill. They never lost a drop of him, because he never left them... But if that's the case, do they really receive him? And if so, how do you go about theologizing that reception? You refuse to make the Blessed Sacrament a transaction, that's how. You say it really is the presence of Jesus, but you don't make it out to be an insertion of Jesus. You say the eucharistic presence is a mirror held up to the church's face so it can see the Jesus it already has. You say it's a dinner with the Jesus who's already in the house. You say any non-transactional thing you can think of - just as long as you say it's a party the church is already at and not some limousine that brings Jesus to the church's door." (Capon, Romance, pp.22-23)We are, to reiterate, missing something during this time when we're not able to physically gather, not able to share communion, physically present to one another. "We are less than what we can be", to quote poet Tim Watson. And yet, we affirm, Jesus is "already in the house" - and profoundly so, if we would but notice him.

Yesterday I was inspired by a good friend and (until recently) close colleague, Revd Becky Stephens, who has just been licensed (over Zoom) as incumbent to a new parish and has had to begin her priestly ministry there without any form of physical gathering of her new congregation. She tweeted:

"I'm spending time this week gathering recorded readings, prayers, music and singing from different members of the @StPeters_SC family. It's just blessing me so much and often bringing a tear to my eye. I may not know the people yet, but there are so many beautiful gifts among them."In this time when 'providing' and 'performing' (not to mention 'possessing') are grabbing a lot of the headlines, both inside and beyond the networks we call 'church', I want to read Becky's time spent in this past week as authentic an outworking of her (ordained) priestly vocation as I have seen anywhere. She has attended to the labour of love of gathering the priestly offerings of others: their noticings, their stories, their reflections, their prayers and praise. She has found a way of creating space to 'hear those offerings to speech', inviting them to be articulated, and receiving them in humble hands to offer, in turn, to God with thanksgiving.

As Capon observes, in a church - a world! - full of priests, the specific vocation of the ordained priesthood is to be "mirrors in which the church [and the world] sees the priesthood it already has". I would add, sitting where I am in the overlap between church and neighbourhood, that this is a vital aspect of the role of community-builder too: 'reflecting back' to our neighbours the gifts that they have, the gifts that they are, and the gifts that are being uncovered and offered in our neighbourhood.

I wonder if this, picking up on Revd Jody Stowell's reflections in Part 4 of my blog on rediscovering the 'uselessness' and marginal nature of ordained priesthood, might be an aspect of that calling (to ordination and/or to community-building) that some of us need to be rediscovering. Without the usual tools in our toolbox - and without our weekly rhythms of physical gathering, for community-building and for eucharist - that gentle work of mirroring, of 'reflecting back', might in some ways be harder work than in 'ordinary time'. But in other ways, as Julie has suggested, this extended time as 'dispersed' church might also be a liberating of all of our priesthoods, a bringing our shared priesthood to the surface - that might make the particular work of gathering and celebrating those offerings much less a burden, and much more an irresistible gift.

No comments:

Post a Comment